Endocrine Disruptors

What Are Endocrine Disruptors?

Endocrine disruptors can be defined as an exogenous chemical, or mixture of chemicals, that interferes with any aspect of hormone action.

Unfortunately, endocrine disruptors are found in many parts of our environment these days. Our endocrine system is a delicate system that can be easily interfered with by endocrine disrupting chemicals. Endocrine disruptors act by binding to cell receptor sites within the body, preventing the correct bioidentical hormone from finding and binding to its associated site. This causes an interruption in the normal signalling and the body is unable to respond effectively. This in turn interrupts the production and receptor site binding of our natural hormones which can contribute to hormone imbalances and disease.

The Different Types of Endocrine Disruptors

Bisphenol A (BPA) was first created in 1891 and was discovered to have estrogenic effects on the body in 1936. BPA is the most mass-produced chemical out of all chemicals, in 2015 15 billion pounds of BPA were produced. It is found in, food packaging, toys, canned food and beverage linings. When BPA in food or drink containers is exposed to high levels of heat, manipulation of repetitious use the BPA can leach into the food and liquids we are consuming from these vessels. Shockingly, a study showed that 93% of American people had a detectable amount of BPA found in their urine. BPA has also been found in human breast milk, meaning babies are also exposed to this chemical just from feeding from their mother’s. Luckily, BPA has a relatively short half-life and is metabolized into non-bioactive forms after 4-5 hours, making it relatively quick and easy to avoid and detox from the body (Gore et al, 2015).

Phthalates and phthalate esters are liquid plasticiser chemical compounds that were introduced in the process of plastic production back in 1920 and contributed to polyvinyl plastic use. The problem with Phthalates is that they are not chemically bound to the plastic, so can easily leach into the environment and be difficult to contain. Phthalates are found in medical tubing, personal care products, toys, vinyl flooring. Phthalates have also been detected in human urine, blood serum and breast milk (Sifakis, Androutsopoulos, Tsatsakis & Spandidos, 2017).

Atrazine is a commonly used herbicide to control weed growth on commercial crops such as corn, sugar cane and sorghum. Public parks, tree farms and golf courses have also been known to use atrazine as a weed control herbicide. Atrazine is an attractive herbicide as it is economical in price, effective for long periods of time, and is a broad spectrum weed killer. Being such a long-lasting herbicide, its no wonder atrazine and its metabolites is the most found pesticide and can be detected in groundwater and drinking water. Atrazine exposure has been linked to carcinogenic effects on the human body. Studies on the effects of atrazine on frogs have also shown the pesticide to emasculate 75% of adult male frogs and turning 1 in 10 frogs into a female frog (COX, 2002).

Polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PCBs) Have been mass produced since the 1920s and have been used in a variety of environments including various building and schools. PCBs can be found in rubber and resin plasticizers, adhesives, inks, paints, flame retardants in mattresses, clothing items and carbon copy paper. PCBs accumulate in the environment and within human body fat, meaning there can be long term adverse health effects. Certain PCBs are considered endocrine disruptors and can exert antiandrogenic, estrogenic or thyroidogenic actions on the body (Gore et al, 2015).

Problems endocrine disruptors can cause

- Weight problems like obesity

- Thyroid problems

- Behavioural problems

- Foetal neural and reproductive defects

- Infertility

- Irregular cycles

- Endometriosis

- Adverse pregnancy outcomes

- Cancers sensitive to hormone changes (ovarian, breast, endometrial and prostate)

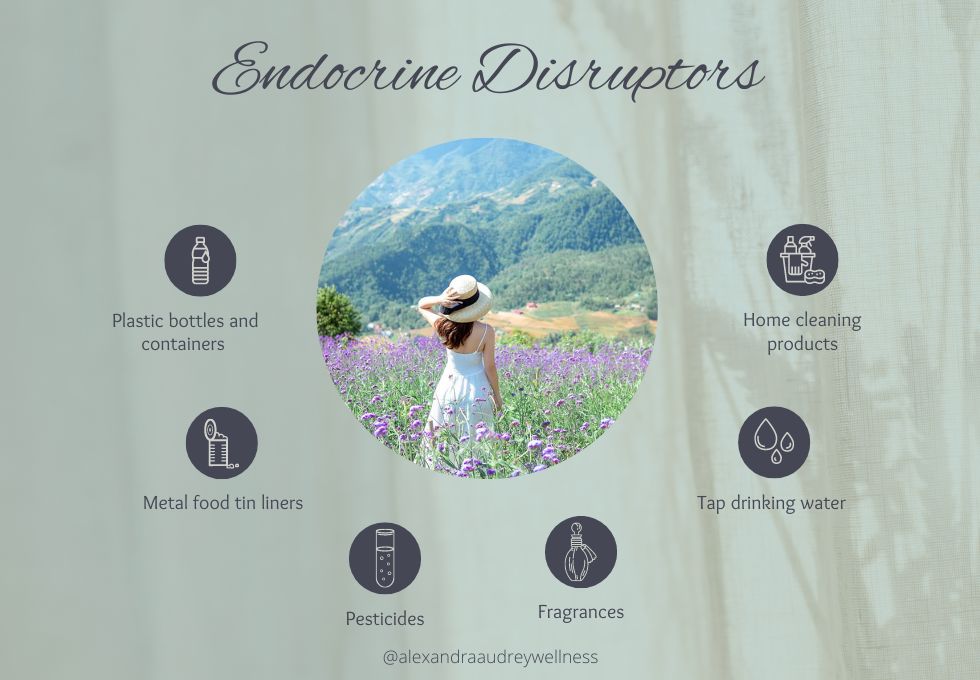

Simple steps to reduce endocrine disruptor exposure

What to avoid

- Plastic bottles and containers

- Commercial/ chemical home cleaning products

- Tap drinking water

- Synthetic fragrances (found in many everyday items)

- Food with high pesticide residue (opt for organic when possible)

- Foods contained in metal tins

Lifestyle tips

Reduce plastic exposure. Swap plastic containers and bottles for glass or stainless steel. Avid heating up food in plastic containers or wrappers.

Buy organic produce and animal foods when able. This will reduce the amount of herbicides, pesticides and chemicals found in food. If this is not possible, focus on buying fruit and vegetables according to the dirty dozen list (shows you which fresh foods have the highest toxic burden and which are worthwhile buying organic) and the clean 15 list (which foods are generally safe to buy conventional). Make sure to buy all organic animal foods (meat, dairy, eggs).

Opt for natural skincare which is low chemical, toxin and fragrance.

Chemicals to be aware of and avoid

- Atrazine (commercial herbicide)

- Benzaldehyde, benzocaine

- Bisphenol A (plastic, toys, lining of cans, food packaging)

- Phthalates ( cosmetics, fragrances, personal products, perfumes)

- Petroleum based polymer derivatives (PEG) cosmetic products)

- Phenoxyethanol

- Triclosan (personal products)

References

COX, C. (2002). The weed killer atrazine feminizes frogs. Journal of Pesticide Reform, 22(2), 8-9.

Gore, A. C., Chappell, V. A., Fenton, S. E., Flaws, J. A., Nadal, A., Prins, G. S., Toppari, J., & Zoeller, R. T. (2015). EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocrine reviews, 36(6), E1–E150. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2015-1010

Sifakis, S., Androutsopoulos, V. P., Tsatsakis, A. M., & Spandidos, D. A. (2017). Human exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals: effects on the male and female reproductive systems. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology, 51, 56–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2017.02.024

Related Posts

Uncovering the Hidden Signs: How to Tell if You Have Impaired Thyroid Function

Dysmenorrhea (period pain) occurs due to the build up of prostaglandins in the uterus. Normal period pain (primary dysmenorrhea) is a mild cramping in…

White and Red Moon Cycles

Moon cycle is the term that can be used to describe the female menstrual cycle. Women have an affinity for the moon,…

Is my period pain normal?

Dysmenorrhea (period pain) occurs due to the build up of prostaglandins in the uterus. Normal period pain (primary dysmenorrhea) is a mild cramping in…

Leave a Reply